Will at centre of legal battle over Shakespeare’s home unearthed after 150 years | William Shakespeare

Published: 2025-08-21 16:28:05 | Views: 15

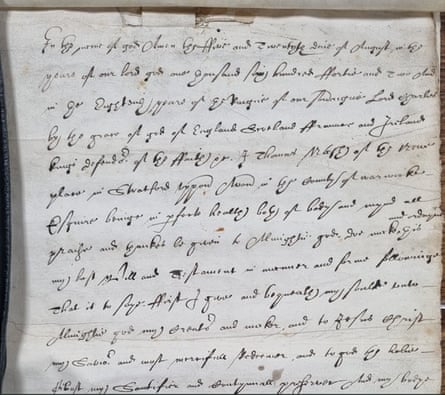

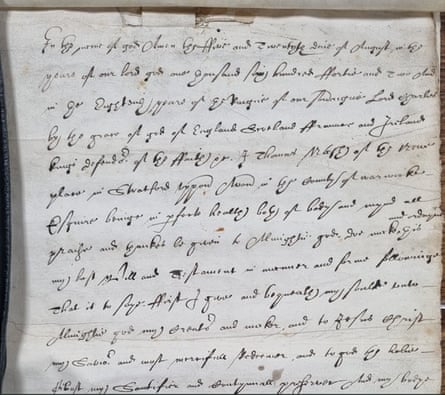

A will that has been lost for more than 150 years and was at the centre of a bitter legal battle by William Shakespeare’s family over who owned the playwright’s final home has been unearthed in an unlabelled box at the National Archives.

The original 1642 document was made by Thomas Nash, who was married to Shakespeare’s granddaughter Elizabeth Hall. In it, he bequeathed New Place, reputedly the second grandest house in Stratford-upon-Avon, to his own cousin Edward Nash.

However, on Thomas’s death in 1647, Shakespeare’s daughter, Susanna Hall, and granddaughter Elizabeth, Thomas’s widow, refused to honour the will, claiming Shakespeare’s own will had decreed the property be left to them and Thomas had no right to bequeath it.

The result was chancery court proceedings, lodged by Edward against Elizabeth, to claim the valuable property.

The Nash will has now been rediscovered in a box of unlabelled chancery documents from the 17th century and earlier by Dr Dan Gosling, a principal legal records specialist at the National Archives.

“It was an incredible find,” said Gosling, who was sorting through the boxes, which were not catalogued or marked with dates or descriptions.

The will was known about in the mid-19th century after being seen by a Shakespeare scholar when originally held in the Rolls chapel. When documents were later sorted it ended up in the unmarked box. “It wasn’t listed, and then was left there for about 150 years or so,” said Gosling.

Shakespeare bought New Place, a three-storied timber and brick dwelling, for £60 in 1597 and lived there until his death in 1616. It had 10 fireplaces, five handsome gables and grounds large enough to incorporate two barns and an orchard.

Thomas Nash made the will while living at New Place with his Susanna and Elizabeth. Though Shakespeare’s will had left his land and the property to his daughter and granddaughter, “it is possible Thomas Nash was making this will in the expectation that he would outlive Susanna and Elizabeth”, said Gosling.

“But what actually happened was he died in 1647. He was very young. Elizabeth was still only 39 and in fact remarried afterwards.” Susanna died in 1649.

Susanna and Elizabeth created a deed of settlement confirming their rights. “Then Edward Nash takes Elizabeth to court. He argues the will of Thomas Nash was proved in the property court of Canterbury, and Elizabeth Nash, as the widow and executrix, was duty bound to abide by the terms of the will and give New Place to Edward Nash.”

Elizabeth appeared at the chancery court to explain the lands and property were granted to her and her mother by “my grandfather William Shakespeare”. As part of proceedings she was asked to produce Thomas’s will, which is how the document eventually ended up in the chancery archives, now held by the National Archives.

The upshot of the proceedings is not clear, but, Gosling said, it appears Edward never got to own the property. When Elizabeth died in 1670, having had no children and ending Shakespeare’s direct line of descendants, her will stipulated Edward Nash would have the right to acquire New Place.

“She uses the words ‘according to my promise formally made to him’, which suggests some spoken procedures were made,” said Gosling. In the event, there is no recorded mention of Edward as owner of New Place, which went to the wealthy landowning Clopton family after Elizabeth’s death and was demolished in 1702.

“It is such a lucky find,” said Gosling. “The chancery case is known about among some Shakespeare scholars and is mentioned in some Shakespeare histories but they always seem to refer back to the 19th century discovery of the will.”

Now the original is documented, catalogued and available to the public for the first time in more than a century.

Source link